Last updated: July 24, 2023

Electric vehicles (EVs) provide benefits to drivers, the environment, and the communities in which they operate. They have no tailpipe emissions and lower life-cycle greenhouse gas emissions than gasoline vehicles. However, EV drivers do not pay gas taxes.

Gas taxes have long been relied on to fund road construction, maintenance, and repair. Both states and the federal government are seeing these revenues decline in real terms due to the increasing fuel economy of vehicles which results in less gas tax revenue and fixed gas tax rates that are not keeping pace with inflation. As a result, many states have developed funding gaps between gas tax revenues and available transportation funding.

Across the country, state legislatures are proposing EV fees and increased registration costs to address a portion of this funding gap. Plug in America believes that EV drivers should contribute to infrastructure costs in a way that is fair, supports transportation equity, and does not disproportionately burden EV drivers or negatively impact EV market transformation.

Background

The federal government and states fund highway construction and maintenance partly through taxes on gasoline and diesel fuel. Revenues from fuel taxes were approximately $32 billion at the federal level and $51 billion at the state level in 2021. Due to several factors, over the years, the revenue has fallen short of what is needed to maintain and construct the roads. Labor and material costs have increased through inflation, but gas taxes at the federal level and in most states have not seen a corresponding increase. Had the federal gasoline tax been indexed to inflation, it would have been 35 cents per gallon in 2021 rather than 18.4 cents. Given the retail gasoline sales of approximately 127 billion gallons in 2021, a federal gas tax indexed to inflation would have brought in an additional $21 billion. This would have made up for the estimated annual federal funding shortfall of $16 billion for 2021.

In addition, vehicle mileage efficiency has improved significantly over the past decade. While providing a host of air quality and economic development benefits, it reduces gasoline sales, thus reducing revenue from gas taxes. Average fleet vehicle fuel economy increased from 18.8 miles per gallon (mpg) in 1990 to 22.8 mpg in 2021 for all light-duty vehicles (SUVs and pick-up trucks included), with new vehicles in 2017 achieving 39.4 mpg for passenger cars and 28.6 mpg for light trucks.

In addition to federal funding, state gas taxes are necessary to support transportation infrastructure. States have their own funding gaps. Estimates of the annual shortfall for some individual states include $9.35 billion for Pennsylvania, $232 million for Maine, and $3.9 billion for Michigan. Beyond these annual funding deficits, some states also have a backlog of deferred maintenance, creating a more significant funding gap.

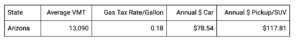

As more EVs take to the roads, states are looking for ways to replace gas tax revenue that EVs do not pay. As shown in Figure 1, thirty-three states have laws requiring additional registration fees or other revenue collection mechanisms for plug-in electric vehicles to offset lost gas tax revenue. Unfortunately, these additional fees are often much higher than what a conventional vehicle would pay in gas taxes.

Figure 1: 2023 Annual Passenger Electric Vehicle Fees

Plug In America’s 3-Step Process for Determining EV Road User Fees

As states consider how to fund highway infrastructure through the shift to electric transportation, we recommend a three-step process in establishing a road user fee for electric or hybrid electric vehicles.

Step 1: Identify Revenue Replacement Baseline

To ensure an adequate funding source for road maintenance as overall vehicle efficiency continues to improve and gas tax returns decline, EV fees should be calculated to replace gas tax as closely as possible using both the average mileage for each state/territory and vehicle weight.

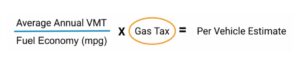

The first step in developing a road user fee proposal in your state is to understand how much the average vehicle pays each year in road user fees. We estimate this by taking the average annual Vehicle Miles Traveled (VMT) in your state by light-duty passenger vehicles and dividing that number by the expected fuel efficiency of an individual or class of vehicle. In Figure 2, we estimate an average fuel efficiency of a car as 30 mpg and an SUV or pickup truck as 20 mpg. This results in the number of gallons of fuel that a vehicle is expected to use in a year. If we multiply the annual number of gallons of fuel used by the gas tax rate per gallon, we know how much to expect that vehicle to pay in annual gas taxes.

Figure 2: Arizona Replacement Revenue for a 30 mpg Car and a 20 mpg SUV/Pickup Truck

Step 2: Address Funding Gaps

To address funding gaps, adjust gas taxes—index gas taxes to inflation.

Every state in the country uses fuel taxes as a mechanism to collect funding for highway infrastructure. Rather than reinvent the wheel, we recommend linking EV road user fees to these mechanisms that are already in place and familiar to policymakers across the country.

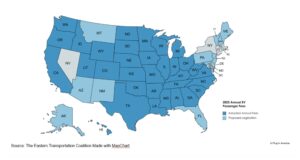

As seen in Figure 3, the gas tax acts as a multiplier in determining revenue replacement for EV road user fees. If the gas tax for any given state is inadequate for meeting highway funding requirements, it should be adjusted in the state legislature. Since it acts as a multiplier for EV road user fees, raising the gas tax will automatically raise the EV road user fee so that both fossil-fuel-powered and electric vehicles will pay the same amount to support safe, smooth, well-maintained transportation infrastructure.

Once gas taxes are set at adequate funding levels, we recommend that states index their fuel taxes to inflation. This allows state legislatures to “set it and forget it” so that they do not have to take valuable time to revisit gas tax rates regularly.

Figure 3:

Step 3: Customize Road User Charges

Customize charges to use available mechanisms and to support state policy goals.

This is where states can get creative and align road user fees to their policy goals. They can also take advantage of available mechanisms, such as annual safety inspections that are already in place, to tailor the cost of using the roads to the travel patterns of individual vehicles. Outlined below are potential policy goals and how states can customize road user fees to reach them.

Decrease vehicle miles traveled: Implement an MBUF (mileage-based user fee).

An MBUF may also be referred to as a Vehicle Miles Traveled (VMT) program. Instead of paying a tax based on gallons consumed, drivers pay for miles driven or VMT. MBUFs are different from tolls in that tolls are facility-specific and not necessarily imposed on a per-mile basis. MBUFs incentivize lower vehicle miles traveled by taxing mileage instead of collecting a fixed fee annually with registration. States can implement an MBUF alone or in conjunction with a flat fee.

Suppose a state wishes to customize EV road user fees to collect them by mileage and use this as a policy lever to reduce miles traveled. In that case, the state can simply take the Per Vehicle Estimate in Figure 3 and divide it by the Vehicle Miles Traveled (VMT). This creates a per-mile fee for electric vehicles.

States with regular vehicle inspections are best equipped to implement a mileage-based user fee. States with annual safety or emissions inspections would collect odometer readings during inspections. Doing so tracks miles traveled, which would be the basis for determining the owed mileage fees.

For states where regular inspections are not in place, EV drivers could pay a flat fee based on the Per Vehicle Estimate in Figure 3 as a default. If a driver is convinced they drive less than the average mileage, they could voluntarily opt to have their odometer read annually. This is similar to using the standardized deduction as a default for paying income taxes with the option to itemize deductions. Without a feasible mechanism to collect regular odometer readings, reconciling mileage at the time of sale could also be used to determine vehicle miles traveled, and the state could provide a refund.

Incentivize smaller, safer, more efficient vehicles: Implement a higher road-usage fee for heavier vehicles.

Heavy vehicles cause the majority of wear and tear on roads. The heavier the vehicle, the more stress it puts on the roads, which leads to increased maintenance costs and shorter lifespans for infrastructure. Gas taxes already account for this, as lighter vehicles tend to be more fuel efficient and pay less in gas taxes. Adjusting EV driver fees based on vehicle size incentivizes drivers to consider smaller, lighter, less resource-intensive cars. A shift towards lighter vehicles could also improve road safety by reducing the risk of accidents and injuries. Weight classifications can be used in the flat EV fee model or in conjunction with an MBUF. In the example provided, there are only two classifications, “Cars” and “SUV/Trucks.” A more granular accounting could use weight or EPA size classes, as shown at fueleconomy.gov.

Make EV fees more progressive: Waive or reduce EV fees for low- and middle-income drivers.

Transportation costs can be a disproportionate energy burden for low-income households. Gas taxes are regressive, meaning they take a larger percentage of income from low-income groups than high-income groups. Since EV fees in this recommendation are based on gas taxes, they are also inherently regressive.

States interested in reducing wealth disparity and promoting equity can scale road user fees based on income or waive the fees for drivers already qualified for social welfare programs like SNAP, WIC, Medicaid, or TANF. It should be noted that offsetting road user fees for low-income drivers will mean less state funding for infrastructure, so alternate funding mechanisms or an overall increase in gas tax will be required to keep state highway funding level.

Incentivize EV adoption: Use the miles per gallon equivalent (MPGe) to determine what the vehicle pays in annual road user fees.

A state that readily recognizes the benefits of driving electric to the economy, human health, and environment may want to incentivize EV adoption, in part, through reduced road user fees for EV drivers. Basing the Per Vehicle Estimate on MPGe instead of the average MPG of a gas car would reduce fees for EV drivers because the vehicles are more efficient than gasoline cars. It should be noted that incentivizing EVs through reduced road user fees will mean less state funding for infrastructure, so alternate funding mechanisms or an overall increase in gas tax will be required to make up the revenue difference.

Conclusion

Every state in the nation collects gas taxes to help pay for transportation infrastructure. As more EVs hit the roads, we propose a process to create a fair and sustainable way to fund highways, roads, and bridges regardless of fuel type. Road user fees can be adjusted from this baseline to make up for funding deficits and support state policy priorities. Using Plug in America’s three-step process to determine EV road user fees, states can meet their transportation funding requirements by identifying replacement revenue, addressing funding gaps by updating gas taxes to sustainable levels and indexing them to keep pace with inflation, and customizing EV road user fees to support state policy goals.

Sources

- Federal Highway Administration, Highway Statistics 2021. Table FE-9, “Federal Highway Trust Fund Receipts Attributable to Highway Users in Each State,” online at https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/policyinformation/statistics/2021/fe9.cfm

- Federal Highway Administration, Highway Statistics 2021. Table MF-201, “State Motor Fuel Tax Receipts,” online at https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/policyinformation/statistics/2021/mf201.cfm

- U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, CPI Inflation Calculator, online at www.bls.gov/data/inflation_calculator.htm

- U.S. Energy Information Administration, U.S. Total Gasoline, All Sales/Deliveries by Prime Supplier, online at https://www.eia.gov/dnav/pet/hist/LeafHandler.ashx?n=PET&s=C100000001&f=M

- Congressional Research Service, Highway and Public Transit Funding Issues, June 2019. Online at https://sgp.fas.org/crs/misc/IF10495.pdf

- Bureau of Transportation Statistics, Average Fuel Efficiency of U.S. Light Duty Vehicles. Online at https://www.bts.gov/content/average-fuel-efficiency-us-light-duty-vehicles

- Pennsylvania Department of Transportation, Pennsylvania’s Transportation Funding Options 2021, Choices for a fair and comprehensive funding solution, March 2021. Online at https://www.penndot.pa.gov/about-us/funding/Documents/TROC-Meeting_03-25-21/PA-Transportation-Funding-Options-2021_3-22-2021.pdf

- Maine Department of Transportation, State Capital Transportation Funding Annual Shortfall, 2019. Online at https://legislature.maine.gov/doc/3433

- Michigan Infrastructure and Transportation Association, Michigan Transportation Infrastructure Needs and Funding Solutions, Executive Summary, March 2023. Online at https://www.house.mi.gov/Document/Path=2023_2024_session/committee/house/standing/transportation,_mobility_and_infrastructure /meetings/2023-03-07-1/documents/testimony/MITA%20Misc%20Docs.pdf

- Consumer Reports, Rising Trend of Punitive Fees on Electric Vehicles Won’t Dent State Highway Funding Shortfalls but Will Hurt Consumers, September 2019. Online at https://advocacy.consumerreports.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/Consumer-Reports-EV-Fee-analysis.pdf

Want to receive our Plug Into Policy monthly newsletter?

You can be the first to know when we publish new reports. Sign up in just a few seconds.